(This is an unedited version of an article published in MusicRow Magazine “Digital Toolbox” Issue, Dec. 2012)

The complexity of music licensing for new formats is nothing new. Do you remember a number of years ago when the courts got the recorded music license rates wrong before Congress stepped in and corrected things? But wait… I’m not talking about the beginning of this millennium. I’m talking about a century earlier; in the early 1900s. Remember that one?

The year was 1909, and a newly published song was “By the Light of the Silvery Moon”, by Gus Edwards and Edward Madden. The popular song was available in sheet music, player piano rolls, phonograph cylinders, and the newly introduced gramophone discs. While Mr. Edwards and Mr. Madden were able to license and collect royalties for their song in print music, they almost missed out on royalties for the other uses. The year before, in February 1908, the Supreme Court ruled that manufacturers of player piano rolls did not have to pay royalties to composers (White-Smith Music v. Apollo Company). The reason? The court ruled that piano rolls were not copies of the song, but instead parts of the machine that reproduced the song. The primary issue was whether or not something was recognizable to an ordinary human being to be a copy of a song. And of course, it would be next to impossible for anyone to simply look at a cylinder punched with holes and recognize music. Further, this same argument could be applied to phonograph cylinders and gramophone discs which were filled with grooves. In 1908, the future record industry had been set up by the Supreme Court to operate royalty free!

Fortunately for songwriters, along came Congress with the Copyright Act of 1909. The Act specifically identified player piano rolls as a “copy” of a song, and introduced a “compulsory license” for what they termed a “mechanical” use, named so because the piano roll was indeed a mechanical machine component to play music. The term and license also applied to the phonorecord cylinders and discs. And the amount of this new license was set at two cents per song, per copy. These royalties were normally paid twice a year, at six-month intervals, due to the laborious task of manual accounting.

The number of opportunities for songwriters was growing. The publishing license world was simple. And the royalty flow was slow.

Over the next 69 years, the music industry saw lots of changes. Phonorecord singles and albums became the format, and stereo sound was introduced. Radio became the popular means to discover new music, and ASCAP, BMI and SESAC (Performing Rights Organizations, or “PROs”) were formed to monitor performance royalties. Television and motion pictures began broadcasting lots of music. Popular artists were selling millions of copies of recorded product. The recording music industry had increased exponentially,… and the mechanical rate for songs remained at two cents.

In 1978, the compulsory license rate increased to $.0275 (although it has since increased to today’s rate of $.091). In the 80s and 90s, new formats, including compact discs were introduced, and the music industry kept on growing. At that time, there were five primary categories of licenses for music; mechanical (recorded), print, synchronization (visual and audio combined), performance, and other, (such as dramatic and grand rights). The royalties were still normally paid twice a year, at six month intervals.

There were now even more opportunities for songwriters. An increasing number of songwriters made more money. The simple world of licensing had become more complex. And the royalty flow was still slow.

Then came digital.

According to IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry), in 2004, there were approximately 1 million digital tracks available by licensed providers, and the digital music trade revenue was $420 million. In 2011, there were close to 20 million tracks available, with trade revenue of $5.2 billion. According to RIAA, in 2000, the music industry was 100% physical product. In 2011, it was about 50% digital. With this rapid growth in digital formats came the added complexities of new licenses for songwriters.

In an attempt to somewhat simplify the multifaceted digital landscape, I will break down the classifications of digital uses to seven categories. Each of the digital music providers known today fall under one or more of these groups.

(1) Permanent Digital Downloads (PDDs)

(2) Limited Downloads (subscription, limited time/plays)

(3) Interactive Streaming (on-demand streams)

(4) Digital Performance (non-interactive streaming)

(5) Ringtones

(6) Digital Print Music / Lyrics

(7) Digital Video

A good example of PDDs would be iTunes. We purchase the song and permanently download it to our devices for future, unlimited, private use. Other digital providers in this category include eMusic, Amazon, Microsoft’s newly introduced Xbox Music, and Rhapsody (until they recently announced they were dropping song download sales). The license rate for songs in PDD’s is the same mechanical rate as for physical product, which is $.091 per song, per copy.

Limited Downloads and Interactive Streaming include subscription models, such as Spotify, Xbox Music, and the new Rhapsody, where the user can access their songs as long as their subscription is active, or they can control the streaming. There are very complex license rates which apply to these uses, which we’ll look at a little later. Digital Performance, which is for the most part not controllable by the user, would include Pandora, XM/Sirrius Radio, iHeartRadio, and other internet radio stations. These entities pay artist and record label royalties to SoundExchange, and the publishers and songwriter royalties to ASCAP, BMI or SESAC. SoundExchange then distributes those royalties almost evenly between the labels and artists for the recorded rights, and the PROs distribute the song royalties to publishers and writers.

Ringtones are licensed at a recently agreed rate of $.24, and Digital Print Music/Lyric reproductions are normally based on a percent of the actual price of the digital print use. Digital Video, which includes YouTube, is licensed using an intricate formula based on advertising revenue.

In early 2009, the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) published an agreement between music industry trade associations for record labels, music publishers and songwriters, and digital music providers, to define five offering types of Interactive Streaming and Limited Downloads, and to set license rates for each. Those types were 1) Standalone non-portable subscription streaming, 2) standalone non-portable subscriptions for mixed uses, 3) standalone portable subscriptions for mixed uses, 4) bundled subscriptions services, and 5) Free non-subscription ad-supported services. Each of the uses have a distinct formula which starts with the greater of 10.5% of the service’s applicable revenue, or a service type minimum, which includes a penny rate for each monthly subscriber and varying percentages of the service royalty. This is all less performance royalties paid to the PROs, and then measured against a royalty pool floor based on the number of monthly subscribers.

Easy enough, right? Well, maybe not. In fact, most of the digital providers ended up hiring a third party company to license, calculate and distribute these royalties to the publishers. Three of the primary third party companies, or “license agents”, are The Harry Fox Agency, Music Reports, Inc (MRI), and RightsFlow, which was acquired by Google about a year ago.

Bet let’s add to the complexity. This year, the same group that defined the 2009 rates added five more mechanical use categories, with their own defined rates, which should be published soon by the CRB and effective beginning 2013. Those are 1) Mixed Service Bundle (if your cell phone service subscription includes a music service), 2) Paid Locker (a subscription locker service, like what iTunes offers), 3) Purchased Content Lockers (a locker, possibly free, made available for purchased downloads or physical product), 4) Limited Offering (a subscription service offering limited streams or downloads for select sets of recording), and 5) Music Bundles (when multiple physical or digital records, or ringtones, are bundled as one transaction). These rates are based on a percentage of revenue (such as 17.36% for some formats), varying on label content and whether the costs are direct or pass through, less performance royalties.

Now, let me first say that I applaud those who were involved in the negotiation of these sophisticated rates. It had to be done, it needed to be comprehensive, it needed to be agreed to by all parties, and timing was critical. And I believe publishers and songwriters were well represented. Well done!

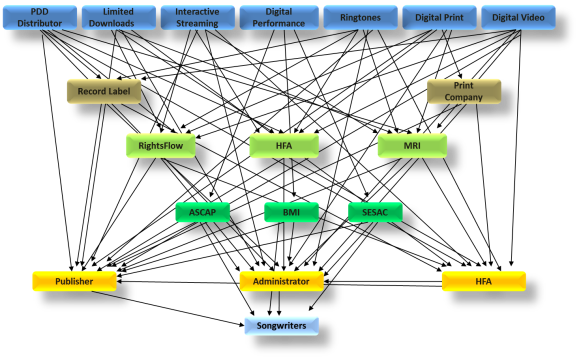

But… the U.S. music royalty structure is beginning to look dangerously similar to the U.S. tax system, which has been called an “extraordinarily complex mess.” I’m beginning to reminisce about the simple two cent rate for a player piano roll. Or at least the $.091 for a simple physical record or an “old fashioned” permanent digital download. (Did I really just use “old fashioned” with PDD?). Not only are the rates next to impossible to understand, the license and royalty flow is becoming a tangled network. I made a diagram using all the players in the digital music license space, from the service providers, the product owners, the license agents, the collection entities, down to the publishers and writers. (This does not include the label and artist royalties paid through SoundExchange). After I painstakingly attempted to connect the flow of licenses and royalties to each appropriate entity, (not counting the ten newly defined mechanical uses), and realizing that there are easily over 60,000 publishers and hundreds of thousands of writers, I stepped back and realized why our license space is in such disarray; and this is just the digital part. (See diagram below).

Current Digital License Space for Publishing

We can do better. Einstein said, “Out of complexity, find simplicity”. As an industry, we’ve successfully set up the first part (complexity). Now let’s find that second step. Maybe we need to change it up a little. Maybe we need to challenge our current perspective a bit.

We can do better. Einstein said, “Out of complexity, find simplicity”. As an industry, we’ve successfully set up the first part (complexity). Now let’s find that second step. Maybe we need to change it up a little. Maybe we need to challenge our current perspective a bit.

The complexity of licensing is definitely a problem area. There is no centralized database of songs. There have been, and continue to be endeavors at setting this up. But unfortunately, the attempts almost always include a large number of players with different agendas. And trying to satisfy everyone dilutes the efforts and ultimately fails, which is what we’ve seen so far. Who will step up with a simple solution?

Another problem area is the proper value of a song, and how that compares to the value of a recording. Publishers want increased fees from Pandora, while Pandora is suing ASCAP and lobbying SoundExchange to pay less. Publishers are arguing that the digital performance royalties paid to labels and artists through SoundExchange are greater than the royalties publishers receive for those same performances. (Pandora’s 2012 annual report shows it paid 49.7% of its revenue to SoundExchange for artist and label royalties, while 4.1% went to PROs for writers and publishers). Publishers and songwriters normally receive a lesser percentage of revenue for any format of downloads than the labels and artists, yet in the world of film & television licensing, most standard licenses for the publishers and masters are of equal value. What is the correct balance?

The timing, efficiency and transparency of the licenses and royalty flow are slow, inaccurate, and a bit foggy. Many companies continue to pay royalties twice a year, a six month intervals, although our advanced computer systems have taken the place of pen and paper ledger entries which existed when this payment structure was initially set up. In a digital age where we have the full data of a sale almost immediately, and digital providers who can easily pay at least on a monthly basis, there are publishers who prefer not to receive the royalties monthly, as it is more difficult for them to process. (Kudos to SESAC who recently announced monthly accounting for some of its members).

One monitoring service stated that they believe 80% of music played on commercial television is unreported or misreported, yet we can use our smart phones to identify the song we’re hearing while sitting in a restaurant. Some digital royalties continue to be paid to publishers without specific songs identified. And I have personally experienced negotiations with a significant digital user who refuses to allow standard audit rights for publishers. Where is the efficiency and transparency we are capable of? I just wonder how long any of us would stay with a bank which concealed this fundamental data. .

We can do better. We should demand better. We allow ourselves to be seduced into accepting lesser accomplishments because they are new and unproven, when we should instead be insisting and delivering on superior achievements which closer match the technology capabilities we possess.

I’m an optimist. I’d rather be optimistic and wrong, than pessimistic and right. (At least the journey would be more enjoyable). And I believe this is an exciting, dawning of a new age in the music industry. More music is available to more listeners, on more devise in more places, than ever before. Is today a better day for a songwriter than any decade before? Absolutely!

So who’s going to figure this out? How can we define the simplicity? Who’s going to win? Einstein also said, “The significant problems we face cannot be solved by the same level of thinking that created them”. So the answer may not be more steps in the same direction. Maybe the answer will be found by looking back at history; or maybe it will be sparked by some small startup company with a new approach; or maybe the answer will be illuminated like it was in 1909, “By the Light of the Silvery Moon.”

John Barker